Pioneers of modern living

The Isokon in north London is a classic example of the quest for viable ways people can live together - a challenge that has exercised the minds of developers and architects for decades and continues today.

Understanding how to foster a sense of community is integral to the creation of new neighbourhoods such as those created in London by Ballymore. At the new Douglass Tower at Goodluck Hope, for instance, there will be purpose-built work and social space and a club with a gym, pool and steam room.

Ideas about the kind of communities we want to be part of have been subject to changing fashions and tastes over the years. But as the success of developments such as London City Island is proving, spaces where people can come together is a valuable ingredient when it comes to choosing where we live.

One of the very first experiments in urban living, the iconic Isokon flats in London’s Belsize Park, is still a model that’s emulated today. Sophisticated and progressive, this remarkably un-British development transformed how people thought about urban living.

Influenced by progressive architectural developments on the continent, Molly Pritchard, a psychiatrist, together with her husband Jack, head of advertising at the Venesta Plywood Company decided to abandon plans to build houses on the site and enlisted Canadian architect Wells Coates to design the Isokon, or the Lawn Road Flats as they were known originally. Built using reinforced concrete – one of the earliest examples in Britain, as was the ’gallery-access’ to the 32 apartments - the emphasis was on compact, thoughtfully fitted rooms. Kitchens were kept purposefully small as the original flats were serviced, with meals available to order from the staffed Isokon kitchen on the ground floor.

Attracting many distinguished residents after it opened in 1934, including the writers Nicholas Monsarrat and Agatha Christie, intellectuals, and even one or two spies, the Isokon became a fixture in Hampstead’s vibrant cultural life. Pritchard also set The Half Hundred Club, a supper club that allowed no more than 25 members who could bring 25 guests. They dined either at the Isobar, at Pritchard’s penthouse flat or occasionally at more exotic locations, such as London Zoo.

“If you try and think back to the mindset of when it was conceived,” says John Allan who as director of Avanti Architects was responsible for the renovation project and is now chairman of the Isokon Gallery Trust. “What Pritchard and Wells Coates were reacting to was all that clutter and excess we associate with those rambling Victorian houses, and thinking that the modern world was surely moving on from that.”

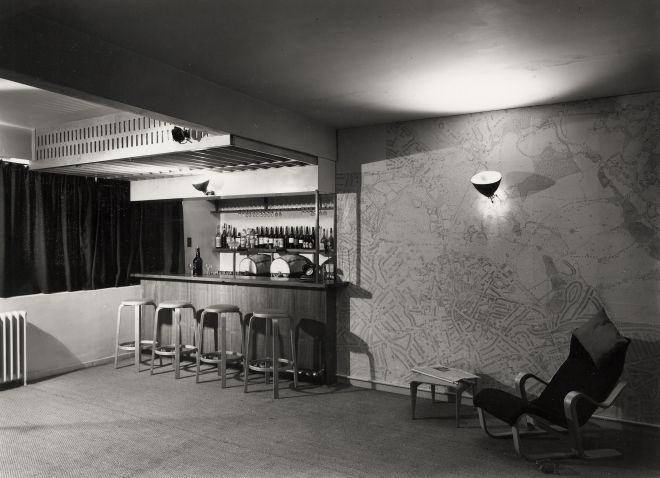

The Isobar became famous as a centre for intellectual life in North London

When the Isokon’s central kitchen was replaced with a café and bar named the Isobar in the late 1930s, designed by Marcel Breuer, this proved far more popular, attracting not only residents, but artists and intellectuals living in Hampstead.

“Almost from the beginning [the Pritchards] conceived the project as a collective enterprise,” says Allan. “He lived in the penthouse apartment and was a very hands on landlord. He knew everybody and surrounded himself with interesting people. That’s the kind of community he wanted to be part of and there was no shortage of interesting people around at that time.”

So important to life at the Isokon were the Pritchards that once they retired the Isokon began a slow process of decline, first under the ownership of the New Statesman and then Camden Council in 1969 and 1972 respectively. Now restored by Avanti Architects for Notting Hill Housing in 2004, the Grade I listed building has been refitted to a standard suitable for a new generation, while staying true to the vision of creating a distinct community in a central location.

“It’s a way of living that suits some kinds of residents and not others, but for the relatively minimalist, mobile professional, it can be very suitable,” says Allan, who with Magnus Englund and Fiona Lamb set up the Isokon Gallery Trust in 2014 and with a small team created the Isokon Gallery in the former garage. Since opening, the gallery, which is used for events and talks has attracted 15,000 visitors.

“We were very keen to have some communal, collective element in the project and if we weren’t going to have the bar back, we can have events and when we do, make sure alcohol is available - Jack and Molly would have approved,” says Allan, adding that the success of the Isokon restoration shows how well thought out and intrinsically valuable the ideas were: “If the latent value of the idea is still there, then that value can be retrieved.”

The Isokon Gallery has free entry 11am to 4pm each Saturday and Sunday from March through October. For further details please visit isokongallery.co.uk